Instagram and TikTok are full of images and reels featuring dancers flaunting their skills. There are some amazing professional artists to watch, but there is a dark side. Often, the reels and pictures you see show young students stretching beyond what their developing bodies are supposed to do. There are lots of over-splits, hyperextension and hypermobile backbends. Most disturbing are the myriad of youngsters crunching over their delicate feet and toes.

Ballet is uniquely demanding in technique and line and all dancers want feet that look like curvy bananas. For the lucky few born with the correct anatomy, it takes a lot of time and work to strengthen. For those who don’t quite have a crescent foot line, it can be frustrating to work slowly and safely. Young students especially can be impatient and rush into unsafe stretching. Unfortunately, the youngest dancers often turn to social media for guidance. There has to be a better way – a more suitable and safer way to achieve one’s goals.

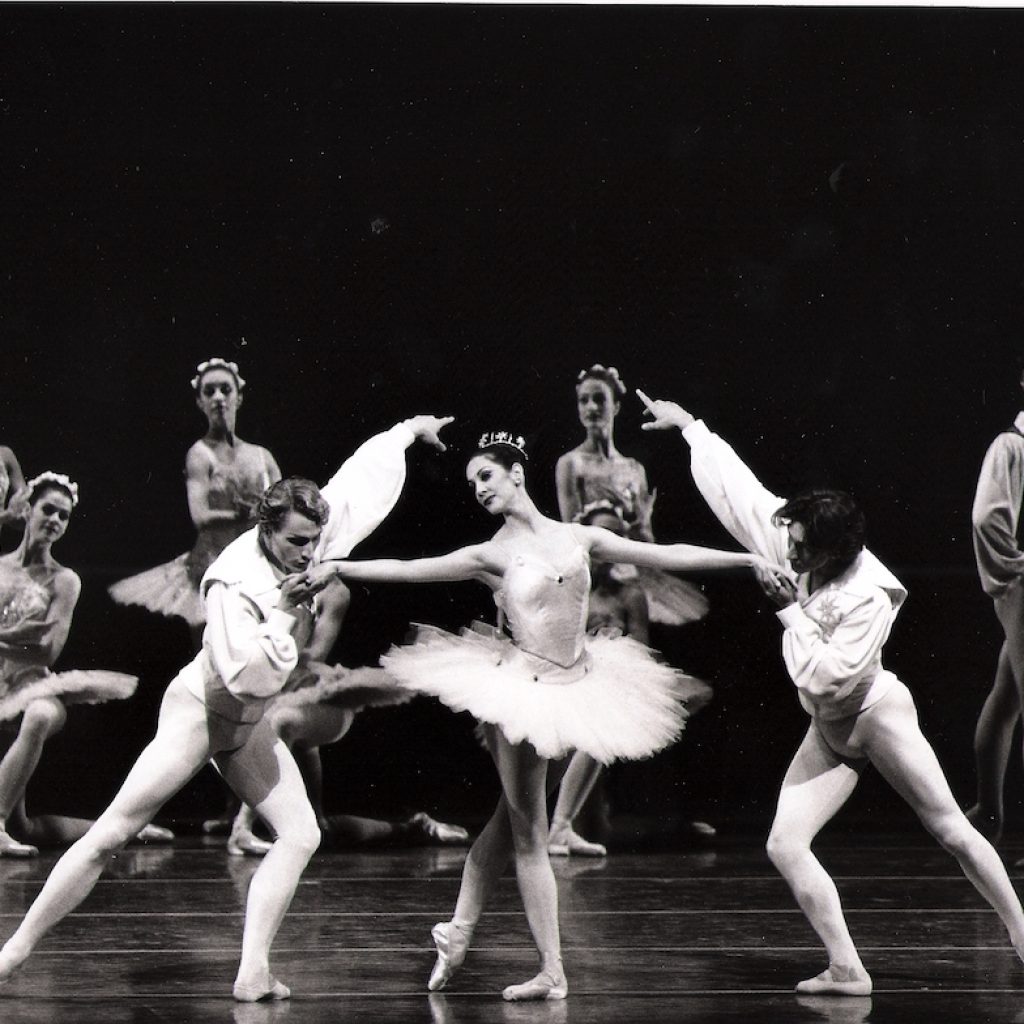

Cynthia Harvey, a former principal dancer with American Ballet Theatre (ABT) and The Royal Ballet and former Artistic Director of ABT’s Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School, shares her expertise. “It’s a difficult process to strengthen the ankle in early training — particular attention needs to be taken during the formative years, and early pointe training,” she says wisely. She goes on to say that the concept of flexibility in the ankle joint is a double-edged sword. Flexibility is helpful as it aids in pointing the foot from the ankle, but too much flexibility increases the risk of sprains. “The instep itself should be no less than 90 degrees from the tibia (a straight line) in order to facilitate a good line and to not impinge from pushing over, particularly in pointe shoes.”

Moira McCormack, MSc, PhD, is a dance physiotherapist and ballet teacher at the Institute of Sport Exercise and Health in London. She is a former professional dancer who coaches dancers back from injury and screens young dancers for the profession.

“The anatomical constraints to the foot and ankle that limit the point position are the shape of the bones and ligamentous tautness,” she explains. She elaborates that the ankle is a hinge joint with a single axis allowing pointing and flexing. The tibia and fibula are bound together, forming the socket that sits over the talus at the apex of the foot. As the ankle points, the back of the talus approaches the back of the tibia. For extreme plantarflexion, there needs to be freedom at the back of the articulation for the ankle to close without restriction. The front of the ankle joint must open freely enough to allow perfect weight-bearing en pointe or high demi-pointe, with a straight line from the knee to the base of support.

Harvey notes, “I cringe when I see dancers standing on their toe joints – over the metatarsal. This stretches the ligaments of the metatarsal and does not increase instep or ankle flexibility.” She adds that stretching the metatarsals and the ligaments in between only weakens the foot. “It would be akin to stretching a rubber band over and over again. Eventually, it gives out.” She also feels strongly that some aspects of social media are not providing the right guidelines for students. “It’s irresponsible. One cannot expect a student to know and understand the dangers of certain stretches, yet instead of listening or asking their teacher, these young people are following the habits of someone not trained in the benefits of proper stretching. It’s just dangerous.”

McCormack echoes Harvey’s statements. “Pushing over on the toes and passively overstretching the front of the ankle closes up the back of the ankle, where a number of delicate soft tissues can be compressed. This can lead to inflammation and swelling, which is difficult to get rid of. We call this soft tissue impingement.”

She explains that sometimes a student with a stiffer ankle has an enlarged bony spur at the back of the talus. If it becomes compressed, it can become irritated and inflamed. This condition, known as posterior impingement, is both painful and requires prolonged, enforced rest and treatment. “This is one of the most frustrating injuries for dancers and physiotherapists alike. Passive stretching does not work. It causes problems. Only hard work and strong muscles working the ankle produce ‘good’ feet.”

Harvey suggests, “Strengthening the feet, including doing exercises to support and uplift the arches, massaging the feet, strengthening the calves, are all tools that help improve a dancer’s foot line.”

McCormack adds, “A perfect functional line for ballet requires enough flexibility to allow the body to balance well over the base of support. The over-arched foot in the young dancer is superfluous, difficult to teach and strengthen and only looks attractive in slow work.” She admits that the profession favors the hyperextended knee and hypermobile foot and selects this type of physique. “You cannot develop what you are not born with, but you can make the very best of what you have by concentrating on technique, control and alignment. All underpinned by strength.”

Both Harvey and McCormack agree that safe stretching can be done outside of the classroom. Harvey likes to show her students the correct way to stretch, with hands placed higher on the metatarsal area, not the toes. “Nothing is going to increase the instep, so continuously stretching won’t alter so much the amount with which one is born.”

McCormack emphasizes that carefully designed foot exercises pay off and should be done every day of a dancer’s life. “They work. Instead of ‘crunching over’ en pointe, the toes brace against the floor, holding you out of the pointe shoe and giving the back of the ankle space, instead of ‘sitting’ in the shoe, which is weak and uncontrolled.”

Harvey cautions, “As teachers, we can’t monitor what they do when they’re out of our sight. We can only inform them of the reasons why some of what they do is not at all beneficial and can be dangerous.” McCormack agrees, noting that dire warnings and anatomical explanations can stop them from overstretching. She incorporates gluteal strengthening exercises to support pointe work and enhance petit allegro, where quick, reactive footwork is required.

Both of these accomplished professionals emphasize the importance of working honestly to achieve one’s goals. McCormack says, “Stretching the capsule, ligaments and tendons over the front of the ankle needs to be done very carefully, but the results can be varied.”

Harvey offers a nuanced perspective: “Ballet is a tough career choice. You can have all the prerequisites but not have a lovely arch. What a shame to have to tell a dancer that they won’t have a career because of that. Now, with consideration of all sorts of physical types, compared to the days when I was growing up as a young dancer, there are areas that are more acceptable than others.”

Harvey concludes on a positive note. “I recommend they use what they do have to their fullest extent.”

By Mary Carpenter of Dance Informa.