It’s basically the norm for professional dancers to have a “second career” after taking their final bow: in choreography, administration, pedagogy, research, something outside of dance entirely, or some combination of those pursuits. Yet, it’s not every dancer who leaves the stage to research dance with individuals experiencing neurological conditions, to help ease their symptoms and brighten their day-to-day lives. That’s exactly what Emily Davis, formerly with Philadelphia Ballet, has done.

She’s now based in Scotland, conducting research in Dance for MS (multiple sclerosis), toward a PhD in that work. Her degree is through the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland (validated by the University of St. Andrews) and Glasgow Caledonian University. Dance Informa speaks with Davis about her career transition, that transition leading her to travel “across the pond”, basic principles of Dance Health, and where she sees it all going from here.

Dr. Bethany Whiteside, Senior Lecturer and Doctoral Degrees Coordinator at the Royal Conservatoire and Davis’ Doctoral Co-Supervisor (alongside Glasgow Caledonian’s rehabilitation expert Professor in Allied Health Science Lorna Paul), will also weigh in. Dr. Whiteside is a leader in the UK’s Dance Health space.

Transitioning from stage to research

Davis feels “lucky” to have performed a range of roles and have had many different experiences while dancing at Philadelphia Ballet (2015 – 2021). She was also able to obtain her BA in Biology at the University of Pennsylvania (Penn) during her time there. As a part of the company’s engagement teaching team, a performer in their Sensory Friendly Nutcracker, and an independent freelance dance practitioner working with community and clinical populations across the city of Philadelphia, she also started to get a foothold in Dance for Health work.

At the same time, she craved even more of that community engagement and witnessing its impact. That, combined with her Penn coursework on social advocacy, as well as time that COVID offered for candid reflection, and her choice got increasingly clearer. “I realized that [community engagement and Dance for Health] is where things were moving for me. I saw my performance chapter closing,” she recounts. “I always want to know the ‘why’…and I realized that I could have a bigger impact in those areas.”

Davis is grateful to have been able to leave the stage by choice; she knows that it can be heartbreaking when it’s not a choice. That was empowering, she says. At the same time, she’s faced many questions and doubts along the lines of “why would you choose to leave your dancing dream?” Davis has had to keep reassuring herself that she’s on the right path.

It’s been a challenge to be more sedentary than she was as a professional ballet dancer, she also notes – but she’s been enjoying movement forms such as spinning and yoga. “I’m moving my body in ways that I wouldn’t necessarily have in my professional dancer days.” Davis does still make it to ballet class, on most Fridays, she says.

Asked if she picked up skills from her dance career that support her in this work, she says that one thing to note there is the discipline that ballet instills. Her PhD is “very self-directed,” and she has to be very self-motivated. Good time management is essential. “Like in ballet, there’s so much work that we put in behind the scenes” in Dance Health research, Davis notes.

Additionally, her professional dance background has given her a baseline comfort in the dance space, as well as a keen perception when it comes to moving bodies – to the “nuances of physicality.” Davis notes that the insight of using movement interviews (dance as an interview form), as a research method, may not have come as naturally to her without that background.

Dr. Whiteside sees Davis’ professional ballet background as part of what makes her great at this work. That combined with being a strong academic, already experienced in Dance Health, and with a new perspective coming from the US, Davis is a valuable contribution to the field, Dr. Whiteside says. “Through an ethnographic approach, she’s respectfully engaging very different communities – with strong ethics at the core. Her research feels novel, timely, and important.” Davis is also the world’s first PhD candidate in this particular area, as far as she knows, Dr. Whiteside notes.

Leaping across the pond

The first step on Davis’ new path was being awarded the Thouron Award fellowship. That would allow her to undertake her PhD through, in Davis’ words, “a perfect pas de quatre”: Scottish Ballet, Glasgow Caledonian University, the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, and the University of St. Andrews. Scotland was just the right place to be for that, as well, with “a lot of excitement” around Dance Health in the country right now.

Scottish Ballet, in particular, has also seemed like just the right partner in this work. Both Davis and Dr. Whiteside affirm that community engagement work is not just an add-on to what they do – rather, it’s “embedded.” For instance, their “SB Elevate®” (Dance for MS) “Time to Dance” (dementia-friendly dance program) have expanded research into, and access to, Dance for Health’s holistic health benefits. Dr. Whiteside has engaged with those programs as an evaluator.

“The puzzle pieces came together” through all of that, Davis says. “Being a ballet dancer is a privilege, and it had to be that right fit in order to leave that career.” That’s not to mention moving “across the pond.” The Visa process has of course been just that – quite the process, and she’s experienced a bit of “culture shock.” At the same time, “Scotland has been a lovely culture to immerse myself in,” she says. Through her research work, she’s also been able to experience “big city” Scotland (in Glasgow), as well as a more rural island community (in Orkney).

All in all, “my transition has been challenging, but the ‘pros’ have far outweighed the ‘cons’,” Davis says with a smile. “I had a good gut feeling when I moved here…and through the people I’ve met and the relationships I’ve built, I’ve gotten confirmation of that feeling.”

Dance Health: Moving in community with ‘dancers’, not ‘patients‘

As wonderfully humble as Davis comes across, it’s clear that she can see the real-time impact of the work in her “second act.” She notes that it can be difficult to capture, in research terms, dance and its holistic health impacts – but she thinks that she can fill in some of those “gaps.”

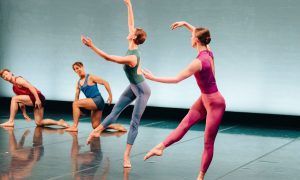

One might wonder what a class like SB Health’s Dance for MS class, SB Elevate®, looks like – and, more specifically, what those impacts are. Very intentional language, designed to be “person-first” and empowering for those who join classes, is of note; all those doing this work through Scottish Ballet – including Davis – call the individuals “dancers”, rather than “participants” or “patients.”

Dr. Whiteside notes that another key part of the approach is following the dancers’ lead when it comes to what style, and how, they want to dance. “It’s more self-led than your standard dance class,” Davis says. “They’re experts on their own bodies and how they move,” Dr. Whiteside affirms.

It’s also important that dancers can take breaks, and even leave class early, without having to explain themselves. “We have to take into account that those with neurological conditions can get fatigued – and to respect that they know their own needs best,” explains Dr. Whiteside.

At the same time, some of Dr. Whiteside’s research demonstrates that some dancers in these classes – specifically those in SB Elevate® classes – appreciate the challenge that they offer, and the sense of accomplishment that can come through meeting that challenge.

Impacts certainly include physical health and function. For instance, dancers in these classes describe using movements from class to accomplish tasks in their day-to-day (such as reaching for something in a cabinet). They note being able to move in new and different ways. “The classes offer a toolkit of movement for their daily lives,” Davis believes.

Perhaps more significantly, as far as the research is starting to demonstrate (it is certainly ongoing), are the mental, emotional and social benefits. Dancers have said that the classes help them to form social bonds and to get practical support. When they can sometimes feel like they’re “losing identities” with the loss of certain physical capabilities, they’re getting a new one: “dancer.”

They can also simply feel an “injection of positivity, a real lift,” Davis says, in the midst of such challenges that result from living with a neurological condition. “Joy is a meaningful outcome,” Dr. Whiteside believes. “It’s not about ‘curing’ a condition…many of these conditions don’t currently have a cure. Rather, it’s about helping individuals live better.”

Stepping forward: Expanding, diversifying, fortifying

Where might it all go from here? For Davis, that could be in many different directions. She thinks that there needs to be more, and broader, research into Dance for Health. “I’ve got many ideas, and I’m keen to expand my research to other clinical populations, as well as into different dance styles and even other art forms.”

She also wants to be part of strengthening the field at large, and expanding access to its offerings. “I want to learn more about the backgrounds of the dancers we’re working with — who’s attending and why, their socioeconomic status and other factors — and from that working to understand and remove any barriers to access,” she says. “I also want to shore up dance as a research method. It still lags behind other arts-based research methods, and it needs an advocate. I want to utilize and keep to my core as a dancer.”

Dr. Whiteside describes some of the ways that the work in Scotland, with all of that excitement behind it, is also shoring up. For one, a recent grant award from The Royal Society of Edinburgh is allowing Dance Health researchers to create a map of where the work is taking place. “There are smaller pockets of it happening, which can feel fragmented and under-resourced,” she notes. That also includes the same, or similar, work happening under different nomenclature and/or fields (for example, psychology and biomechanics), she adds. “Partnerships can pay huge dividends if they’re able to develop.”

Coming full circle to dance as an art form, Dr. Whiteside describes how Dance Health even has potential to feed back into choreography, performance and teaching. For example, Dance Health research can enrich teaching artistry at a place like the Royal Conservatoire.

“It’s not stage or bust,” Dr. Whiteside reminds us; we can think more expansively about what a life in movement can be. Just like Emily Davis demonstrates, there are so many different ways to share dance with the world – and we can shape how that unfolds.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.