The dance field has accomplished some incredible feats, and is pushing forward into a strong future – despite some pesky and perennial challenges. Preservation of an ephemeral art form that words can fail to capture, with a choreographer’s original vision intact, is certainly one of those challenges. Another is the conundrum of copyrighting something so ineffable – and, therefore, how easy it can be to use another choreographer’s work without their consent.

Movement notation systems, such as Benesh Movement Notation (BMN), can help address these and related challenges. That’s not to mention fostering greater bold innovation in the field, and a healthier ecosystem within it by supporting emerging choreographers’ work. Dance Informa speaks with Anders Ivarsson, AIChor FIChor, to learn more about BMN — what it is, how it bolsters the field, what it’s like to study and use it, and more. Ivarsson serves as Interim Head of Benesh International with the Royal Academy of Dance (RAD).

What is Benesh Movement Notation?

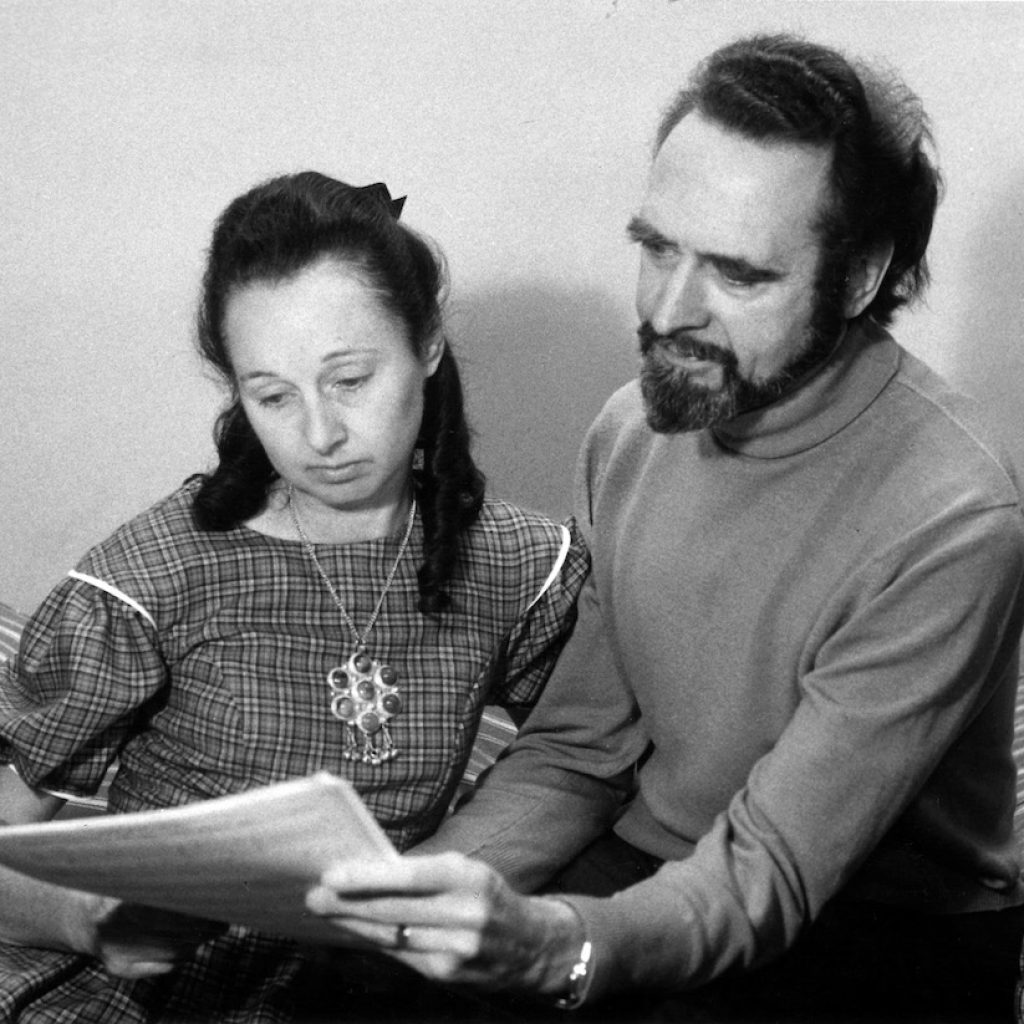

BMN, the brainchild of Rudolf and Joan Benesh, was first published in 1956. “Most widely used in the recording and restaging of dance works,” practitioners of the form have written over 1,750 scores – used in “research, teaching dances, …and for analysing movement.” It is the official movement notation system of the Royal Academy of Dance. “The set exercises and dances in the RAD syllabi are published in BMN, as this enables teachers to study the work in a common language and in more detail than is possible from word notes or videos alone,” the RAD states on its website.

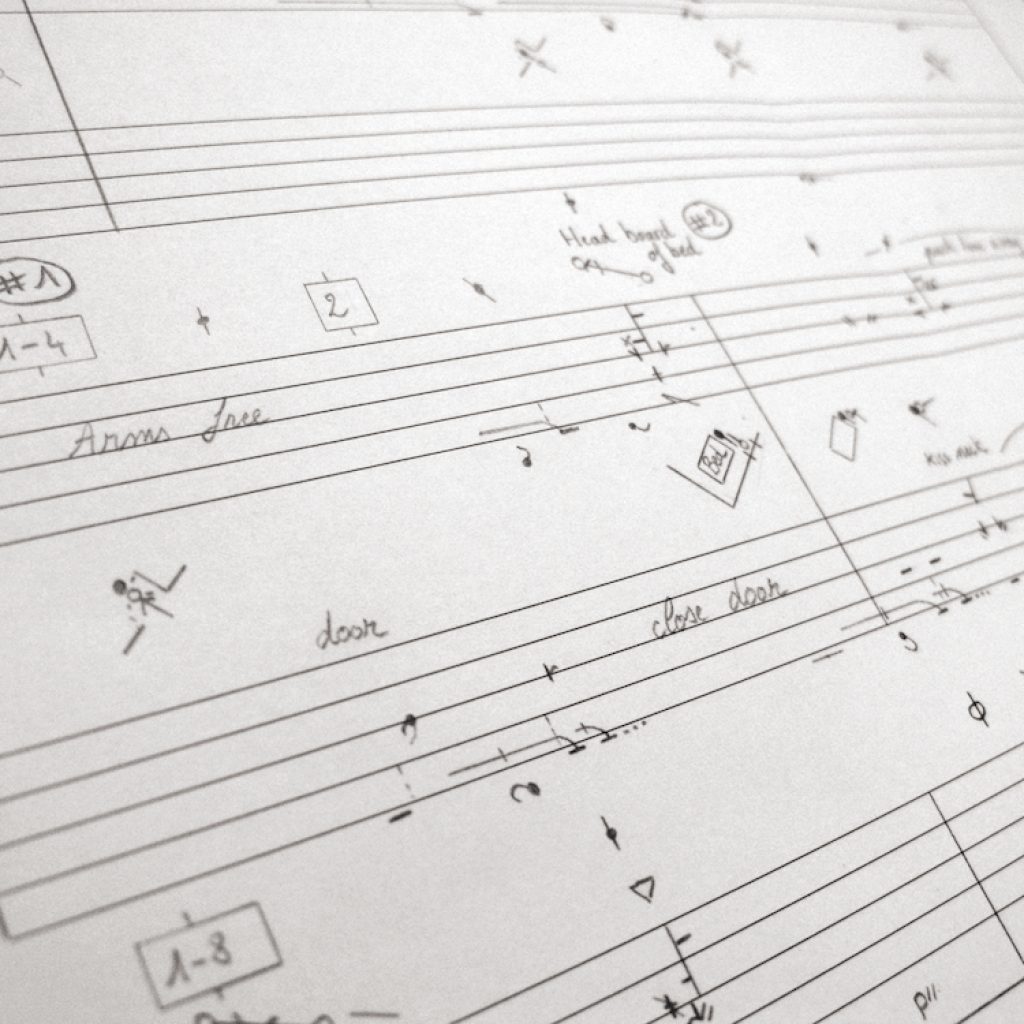

Through BMN, “choreologists document the movement, and the choreographic intention, in a detailed and systematic way,” Ivarsson explains. Movement notation systems “distill the complexity of three-dimensional movement into a two-dimensional representation,” he adds. One way of seeing these systems, he believes, is that they can create “mathematical reductions of a body in three-dimensional space projected onto a two-dimensional plane.”

That’s not math as in algebra or calculus, but “the complexity of movement in three-dimensional space (four if you include time)….reduced into a form which can be clearly communicated using only two dimensions” – in other words, on paper, Ivarrson explains. The system itself gets a bit complex, necessarily so, to translate all of those details. Ivarsson explains it best:

“In a Benesh score, the two-dimensional plane is called a ‘frame’ and, in its simplest form, a Benesh score consists of several frames, one after another, on a horizontal [music] stave. As in music, this horizontal stave serves as the axis of time, with movements plotted from left to right to indicate their sequence over time. The three dimensions of the Cartesian coordinate system are communicated by using the three basic signs: the In Front, Level, and Behind signs ( | , — , ● ), and their precise placement within the frame. This allows the choreologist to accurately record the movements, ensuring easy cross-reference to the music, or other key elements of the performance. In this simplified representation, each position is carefully plotted and assigned a specific position within the frame, like how a cartoon strip depicts a sequence of actions.”

Ivarsson is describing choreology there. He cites The Oxford English Dictionary’s definition: “the study and description of the movements of dancing.” That includes the movement, structure and even the cultural context of the art form, he adds. Those who execute choreology are choreologists (a term Ivarsson also used above). These individuals are key in dance research and analysis. “They help in preserving the history, legacy and significance of dance.”

Why movement notation: Learning, sharing and nurturing dance

Ivarsson underscores just how central that legacy, history, tradition are for dance as an art form. When we preserve the history of dance, we preserve “the stories, emotions and expressions of previous generations,” as well as the “cultural identity of the art form,” Ivarsson affirms. Perhaps paradoxically, it might seem at first, that’s actually necessary for the art form to innovate and progress. That’s because the past serves as a foundation, from which the art form can “evolve over time, incorporating new techniques and ideas” (like all art forms do).

Such preservation requires the “effective communication and documentation of movement” – and that’s just what movement notation systems such as BMN can offer, Ivarsson says. That documentation – versus word-of-mouth passing on what was learned in rehearsal – allows for precise, accurate restaging, as well as “deeper understanding of the choreographer’s vision.” Movement notation also assures that all subsequent performances of a particular work reflect those qualities and nuances, says Ivarsson. “Choreographic intention of movement [is] maintained,” and dance works are sustained for future generations.

Dance’s ephemeral quality calls for such purposeful preservation. Otherwise, the art form’s treasures are lost. “Dance is a transient art form, existing only in the moment of its performance. By preserving dance through notation, future generations can study and recreate these works, keeping them alive and relevant,” Ivarsson says. He highlights how that’s particularly meaningful with works “that are at risk of being lost or forgotten.”

One might wonder why all of this can’t be captured on film, now that we have that technology. (We certainly haven’t had it for all of dance’s history.) “A film recording of a performance is actually a recording of one performer’s artistic interpretation of the movement,” Ivarsson points out. A Benesh score, on the other hand, captures the essence of that movement – all of the shades and subtleties that make it truly magical, in the ways that a choreographer made it magical.

Why movement notation: Copyright protection

Benesh International also “supports the dance profession by preserving choreographic copyright.”

Why does choreographic copyright matter, you may ask? “It protects the creative expression and intellectual property of choreographers,” notes Ivarsson. “Without copyright protection, anyone could simply copy these works and claim them as their own – depriving the original choreographer of their due recognition and financial reward.” Choreographers invest a massive amount of time in their work, Ivarsson adds. They pour in their creativity and originality. These are all ingredients needed for dance to thrive – and copyright protects them.

Copyright also preserves choreographers’ original vision; it gives choreographers “exclusive rights” to their works, thus “ensuring that their artistic creations are not diluted or distorted by unauthorised adaptations or variations,” Ivarsson explains. That maintains choreographic accuracy. That, in turn, facilitates appreciation and interpretation of a given work that aligns with a choreographer’s vision.

It’s not only about what choreographers have already created, but about works yet to come; Ivarsson describes how copyright “encourages innovation and creativity within dance…and a dynamic and vibrant dance scene where new styles and techniques can emerge, flourish and inspire others.” Why? How? When choreographers know that they have these legal protections, they’re “more likely to take risks and push the boundaries of their art form when they know their work is protected.”

Studying Benesh Movement Notation

Studying BMN is open to those looking to work as a choreologist as well as those simply seeking to sharpen their dance knowledge and artistry. Amongst other skills, “BMN hones your analytical skills to analyse movement,” Ivarsson notes – which students of the system have testified to. It can also help hone technique and deepen dance artistry; Iversson notes how RAD teachers “have observed that students who learn BMN experience an improvement in the quality of their movement.”

Ivarsson is clear: if one does aspire to become a professional choreologist, they should be aware that the path there is both rewarding and rigorous. Again, he explains something complex well:

“The full program consists of the Professional Award in BMN (PABMN) followed by the Post Graduate Diploma in BMN (PGDBMN). Typically, it takes between three and six years to complete the PABMN and normally another year for the PGDBMN. However, since both programs are part-time and offered through distance learning, dancers can begin, and even complete, their studies while still actively dancing.”

Yes, it sounds intense, but Ivarsson – for his part – thinks that studying the system is not as hard as it might first look. The system has certain baseline theoretical concepts – and “once one grasps the progression of those, it is much easier to understand the more complicated aspects of BMN,” he explains.

A good place to start, he thinks, is Benesh International’s introductory course “BMN for Ballet”. It can offer enough of a taste of the discipline, and studying it, “to see if it is something they indeed want to do,” says Ivarsson.

If they do decide to study the system, they can be part of preserving past works, nurturing artists and artistry of the present, and helping the art form become even more relevant and thrilling in the future. How exciting!

For more information on Benesh International and the Benesh Movement Notation, visit www.royalacademyofdance.org/benesh-international-benesh-movement-notation.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.